We are proud to present our latest Artist of the MonthAn interview with Simon Richardson

- theartsproject1

- Oct 3, 2023

- 10 min read

Simon Richardson at the Emerald 20 exhibition (photo by Peter Herbert)

INTRODUCTION

HEAD TO HEAD: DRAWN TO PAINTING

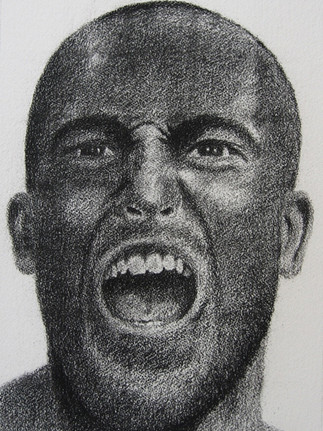

"Simon Richardson first exhibited with The Arts Project in 2013 Loudest Whispers. A thread in his early work that I found fascinating was his compelling and visceral drawings of male heads. Neither purely photorealist or abstract, these drawings inhabited a shifting space somewhere between the two. It has been intriguing to see how Simon has developed his male head images since then, going from the tonality of drawing into the colour of painting. One of Simon's paintings in 2018 Loudest Whispers, 'Two', was chosen for the 250th Royal Academy Summer Exhibition curated by Grayson Perry. Looking forward, the male head and how we view and respond to it seems set to continue being a key theme in Simon's work. In this interview we find out about the how, why and what's coming next in the journey of a remarkable talent. The Arts Project is delighted to offer Simon our support and the opportunity to exhibit his work with us as it continues to evolve."

Peter Herbert

Curator Manager

THE ARTS PROJECT

'Untitled' - Loudest Whispers 2013

‘Two’ - Loudest Whispers 2018

1. Your work shows development and subtle changes in relation to the male head that introduces meanings and moods that are compelling. Can you tell us what drives your fascination with presenting the male head as a form of portraiture?

I suppose I’m not sure if I think my male head images are a form of portraiture, at least as I understand it. I’ve never met any of the people in my work (they haven’t sat for me in the traditional sense) so there’s not been the interaction that can develop around portraits, such as Martin Gayford describes when he sat for Lucien Freud. Alongside that, through having men as the subject of my work a whole host of assumptions - artistic, cultural, social, you name it - are inevitably brought into question. Art (as the Guerrilla Girls have notably pointed out) has been largely about male artists painting women. So you immediately introduce a whole new set of dynamics if you’re a male artist drawing or painting men, particularly if you’re a gay man as I am. There’s a potentially endless source of material to explore in all that which goes beyond just portraiture.

That said, I knew I wanted the men in my work to be recognisably of now - I didn’t want them to be mythological heroes or epitomise some classic ideal of male beauty or anything like that - which may be why some people’s initial association when they see my work is to portraiture. But there was a practical issue in the focus on the head too. My work is never larger than A1 size - or not so far. Given that amount of space to work with, I felt that doing a male figure full or three- quarter length could quickly become limiting both in composition or the detail possible. It was where photography was an influence. I decided to crop right into the head or the face, as a photographer might do, to fill up the picture plane. Having made that decision a whole number of things then followed on in the making of the work. When I’m close up to the surface what I can see is a collection of marks, shapes and tones but then, standing back, the face or head emerges. It’s almost like there’s two pieces of work going on at the same time. That in itself is an absorbing process to be involved in.

‘Behind Blue Eyes’ - Loudest Whispers 2019

In fact I find the whole process of looking - and what that means - fascinating. A lot of current art theory focuses on ‘the gaze’ but implicit in this is the idea that the viewer is the one doing the looking and the image is simply a passive recipient of that. I’ve become interested in other traditions where the image is understood to look back or hold the viewer in its gaze. An example of this occurs in darshan in Hinduism where the looking functions in a way that’s intended to be reciprocal. Obviously that’s a very particular religious and cultural context, but things like that helped open up my thinking about how people might look at the male head images - and how they might look back. In portraiture, by contrast, the emphasis is generally on the likeness to the sitter and how well the artist’s technique catches that, which (as you can see by now) isn’t really where my interest lies.

2. Tell us more about variations on the original black and white media of the early work. What is behind the gradual changes involving colour, technique and interest in the body, which is linked to the head and (in some newer work) the body form as well as the head?

That’s really about me exploring different types of media. To begin with I used charcoal or conté crayons because they were fairly easy to use without making too much mess. I don’t have a studio or other space set aside for art making so I tend to use materials that can easily be put away when I’m not using them. I wanted to explore what ‘drawing’ as a process could be and trying out different kinds of media was part of that. I was looking at black and white photos and seeing possible links with drawing media like charcoal or conté crayon, which are effectively monochrome. I tried oil pastels too. I was able to build up layers and produce really lovely dark tones with them. They were a bit of a nightmare to use though because the fixative took ages to dry on them.

‘Head #4’ - Loudest Whispers 2016

‘Head #11’ - Loudest Whispers 2017

The move into paint and using colour was really just a continuation of that explorative process. Paint is generally a more forgiving medium and you can work over any mistakes you make, whereas in charcoal or conté crayon it’s pretty much game over. Colour opens up endless possibilities with the different hues and values you can create and in trying out how different colours work with each other. It introduces its own kind of allure or sensuality to the male head or figure. If you compare a painting I showed in 2017 Loudest Whispers with a drawing in the exhibition a year before (above) it’s not that either one is better but the medium in each image brings its own kind of sensuality; whether in the open mouth in the drawing or the five o’clock shadow framing the mouth and jaw in the painting.

3. Your training and experience as an art therapist must bring challenges and rewards through the work you do with people. What kind of new viewpoints has it given you and can you tell us about the kind of influence it has had on your creative life?

I think it’s had a considerable influence on how I think about ‘art’ and particularly the ways in which it can enable meaningful (and often very personal) communication, both for someone internally with themself and externally with others in their lives. My work in art therapy has helped me think about what can be meant when we talk about ‘art’ too. I no longer see it as just being about creativity and artists producing beautiful objects for other people to admire and own. It’s helped me think about the work I produce in quite a different way and I’m often aware of how an image has a significance for me beyond its composition or content. A key area of interest for me as an art therapist has been the ‘participant observer’ role. From early on I was interested in how interacting through art making might help with establishing trust and communication between client and therapist. I made this the focus of my MA research and the work I did on clinical placement at one of the old long-stay hospitals for people with learning disabilities. Many of the patients had spent a lifetime there and had become very institutionalised. I used the art making process as a way to engage with them more equally, including us making work together. Through this people became able to participate in the sessions in a way that was assumed not to be possible because of their learning disability. It helped me see how ‘art’ can work in so many ways and that’s been something I’ve taken through to my own creative practice. I have written about the art therapy sessions I have run with people affected by homelessness in the chapter ‘Making Space’ which I contributed to Contemporary Practice in Studio Art Therapy. I have also written about my one-to-one work with someone with ME and mental health issues in ‘Completing the Picture’ in Art Therapy with Physical Conditions.

4. Your work raises questions about technology and media. Any thoughts on the power of the camera lens in relation to how we view ourselves and others?

I always find the way that question is framed interesting because, for me, the camera lens is just a mechanical device. The lens can make a difference depending on what kind it is, of course, but in the end it’s the person behind the lens that matters. The real issue is how accessible photography is nowadays (every smartphone has a camera on it) with millions of images being uploaded to the internet every day. How that’s impacted on my work is in the content of digital imagery, in particular the selfie, and how digital images are made, namely with pixels.

Charcoal selfie #1 - Loudest Whispers

Charcoal selfie #2 - Loudest Whispers 2015

Susan Sontag notes that photographs show things retrospectively because the moment they capture has gone. That makes me wonder if selfies are actually some sort of memento mori, with people catching themselves in a moment before it goes. Making a charcoal drawing in response to a digital selfie is, in one sense, working at the opposite end of the scale in that a selfie is made with a click of a button, whereas a charcoal drawing takes time. However, I found a personal point of convergence between drawing and digital photos in the pixel. I ended up using drawing paper with a rough surface to help me make the ‘pixely’ charcoal marks I wanted, bringing old and new together.

Something else I noticed about selfies is that they draw you into a kind of community on the internet that involves sharing (uploading) an image, someone seeing and using that image in some way, then uploading their image to the internet where someone else can use it. No-one knows quite how this will all end as potentially anyone can join in. This is effectively what happened with a painting I showed in 2021 Loudest Whispers (below). I had seen and downloaded an image I liked from the internet. It’s a man in his car and in a very understated way everything in that image is about how he wants to be seen, which is relaxed, confident and in control.

Photo from Instagram

'Head #21’ - Loudest Whispers 2021

I liked the slightly off three quarters turn of his head and it was that I took into my painting. I didn’t want to just copy the image, so I made the angle of the head vertical to the bottom of the picture and used a plain colour background rather than the car interior. When the finished work was exhibited people uploaded photos of it to social media (including selfies they took in front of it). So the process came full circle but maybe, who knows, someone saw one of those images and that gave them an idea and the whole thing started all over again.

5. Are you self-taught or trained and are there studies or theories that interest you which underline the background to your work? If so, what triggered this interest?

It’s probably six of one and half a dozen of the other really. I’ve done art and design training courses (including Fashion and Art Therapy) but I also think there’s a sense in which anyone who makes art becomes self-taught to some extent as they develop their own style. Over the years I have been exposed to a range of theories and approaches including anthropology, design theories, semiotics, philosophy of art, psychoanalysis, and psychology among others, which have all helped in developing my thinking.

However, when it comes to influences on my work and how I want to develop it then primarily that’s going to be about seeing the work of other artists and learning from them. An example of this is ‘Swimming in Monet’s Pond’, which I showed in 2019 Loudest Whispers and was based on one of Claude Monet’s paintings of his garden in Giverny. I came to see that my initial idea of ‘swimming’ in Monet’s pond was really thinking about looking and the ways in which a viewer immerses themself in a painting, becoming submerged in the colours and diving into the shapes and textures.

‘Water Lilies’ - 1914-1917, Claude Monet

‘Swimming in Monet’s Pond’ 2019

The way in which the eye travels around pictures is like swimming in them, going backwards and forwards across the surface, exploring and responding to the artist’s work. Painting my picture also became a way of learning from Monet and developing my own vision rather than simply copying him. It helped me look at and experience his work quite differently than if I’d encountered it in a gallery or read the catalogue description.

6. Where do you think your work is heading as you explore your subject that you can share with us?

In one way I am never quite sure where my work is heading but I am aware of a couple of strands that I’d like to try following up. One is that it feels like a good time to look at the work I’ve done so far and revisit some of those past ideas and do more with them. I put three male head drawings into the Pixels and Pigments exhibition last year and had a very positive reaction.

‘Head’, A1 size - 2016, Pixels and Pigments

I haven’t done a new head drawing since 2017 (when I began focusing on working in paint) so I’d like to pick up where I left off with that. When I started doing paintings I realised that I’d need to take some time regaining the skills and confidence I used to have. That’s felt to be a worthwhile process and I think I’m up to speed now, so the time feels right to broaden out the media I use and start drawing and painting. The other way I’m looking to develop is more compositional. We’ve talked about the male head images and how they can interact with the viewer but I’m aware that they are single figure works.

'Two' - Loudest Whispers 2014

'Two' - Loudest Whispers 2022

Over the years I’ve made a smaller number of pictures with two men in them, which introduces not just compositionally spatial relationships but how they might be relating to each other emotionally or psychologically. What I want to avoid is falling into a narrative approach where I end up doing something almost like domestic interiors. I’ve been looking at the work of artists like Francis Bacon or Marlene Dumas to see how they overcome this and I can see that I need to keep my settings sparse when there’s two figures (or even one) in them. I’ve been trying this out with varying degrees of success over the past couple of years and it’s definitely something I’ll continue to focus on. It all depends on having the time available, of course, but I am aiming for there to be new work encompassing some of these ideas for Loudest Whispers in 2024.

Photo by Peter Herbert taken at the Emerald 20 exhibition

Thank you Simon for being our Artist of the Month.

You can follow Simon at:

Instagram Simon is one of the artists talking about their work in Anna Bowman's film Real Life and Dreamworlds about last year's 'Pixels and Pigments' exhibition.

Comments